Cancer:

Breast, colorectal., brain, leukemia, acute myeloid leukemia (AML), melanoma, lung, glioblastoma, prostate, fibroblast carcinoma

Action: Multi-drug resistance, apoptosis, anti-cancer, chemotherapy sensitizer, CYP450 regulating, inhibits growth and metastasis, down-regulates MMP-9, enhances 5-FU, anti-inflammatory

Inhibits Growth and Metastasis

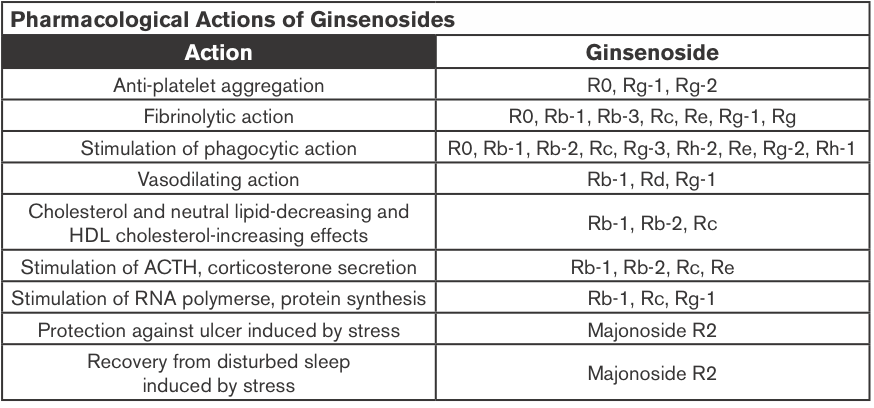

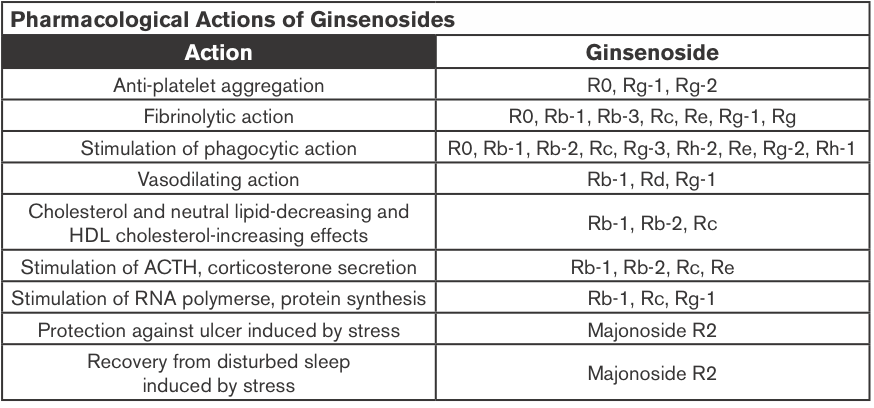

Ginsenosides, belonging to a group of saponins with triterpenoid dammarane skeleton, show a variety of pharmacological effects. Among them, some ginsenoside derivatives, which can be produced by acidic and alkaline hydrolysis, biotransformation and steamed process from the major ginsenosides in ginseng plant, perform stronger activities than the major primeval ginsenosides on inhibiting growth or metastasis of tumor, inducing apoptosis and differentiation of tumor and reversing multi-drug resistance of tumor. Therefore ginsenoside derivatives are promising as anti-tumor active compounds and drugs (Cao et al., 2012).

Ginsenoside content can vary widely depending on species, location of growth, and growing time before harvest. The root, the organ most often used, contains saponin complexes. These are often split into two groups: the Rb1 group (characterized by the protopanaxadiol presence: Rb1, Rb2, Rc and Rd) and the Rg1 group (protopanaxatriol: Rg1, Re, Rf, and Rg2). The potential health effects of ginsenosides include anti-carcinogenic, immunomodulatory, anti-inflammatory, anti-allergic, anti-atherosclerotic, anti-hypertensive, and anti-diabetic effects as well as anti-stress activity and effects on the central nervous system (Christensen, 2009).

Ginsenosides are considered the major pharmacologically active constituents, and approximately 12 types of ginsenosides have been isolated and structurally identified. Ginsenoside Rg3 was metabolized to ginsenoside Rh2 and protopanaxadiol by human fecal microflora (Bae et al., 2002). Ginsenoside Rg3 and the resulting metabolites exhibited potent cytotoxicity against tumor cell lines (Bae et al., 2002).

Ginseng Extracts (GE); Methanol-(alc-GE) or Water-extracted (w-GE) and ER+ Breast Cancer

Ginseng root extracts and the biologically active ginsenosides have been shown to inhibit proliferation of human cancer cell lines, including breast cancer. However, there are conflicting data that suggest that ginseng extracts (GEs) may or may not have estrogenic action, which might be contraindicated in individuals with estrogen-dependent cancers. The current study was designed to address the hypothesis that the extraction method of American ginseng (Panax quinquefolium) root will dictate its ability to produce an estrogenic response using the estrogen receptor (ER)-positive MCF-7 human breast cancer cell model. MCF-7 cells were treated with a wide concentration range of either methanol-(alc-GE) or water-extracted (w-GE) ginseng root for 6 days.

An increase in MCF-7 cell proliferation by GE indicated potential estrogenicity. This was confirmed by blocking GE-induced MCF-7 cell proliferation with ER antagonists ICI 182,780 (1 nM) and 4-hydroxytamoxifen (0.1 microM). Furthermore, the ability of GE to bind ERalpha or ERbeta and stimulate estrogen-responsive genes was examined. Alc-GE, but not w-GE, was able to increase MCF-7 cell proliferation at low concentrations (5-100 microg/mL) when cells were maintained under low-estrogen conditions. The stimulatory effect of alc-GE on MCF-7 cell proliferation was blocked by the ER antagonists ICI 182,780 or 4-hydroxyta-moxifen. At higher concentrations of GE, both extracts inhibited MCF-7 and ER-negative MDA-MB-231 cell proliferation regardless of media conditions.

These data indicate that low concentrations of alc-GE, but not w-GE, elicit estrogenic effects, as evidenced by increased MCF-7 cell proliferation, in a manner antagonized by ER antagonists, interactions of alc-GE with estrogen receptors, and increased expression of estrogen-responsive genes by alc-GE. Thus, discrepant results between different laboratories may be due to the type of GE being analyzed for estrogenic activity (King et al., 2006).

Anti-cancer

Previous studies suggested that American ginseng and notoginseng possess anti-cancer activities. Using a special heat-preparation or steaming process, the content of Rg3, a previously identified anti-cancer ginsenoside, increased significantly and became the main constituent in the steamed American ginseng. As expected, using the steamed extract, anti-cancer activity increased significantly. Notoginseng has a very distinct saponin profile compared to that of American ginseng. Steaming treatment of notoginseng also significantly increased anti-cancer effect (Wang et al., 2008).

Steam Extraction; Colorectal Cancer

After steaming treatment of American ginseng berries (100-120 ¡C for 1 h, and 120 ¡C for 0.5-4 h), the content of seven ginsenosides, Rg1, Re, Rb1, Rc, Rb2, Rb3, and Rd, decreased; the content of five ginsenosides, Rh1, Rg2, 20R-Rg2, Rg3, and Rh2, increased. Rg3, a previously identified anti-cancer ginsenoside, increased significantly. Two h of steaming at 120 ¡C increased the content of ginsenoside Rg3 to a greater degree than other tested ginsenosides. When human colorectal cancer cells were treated with 0.5 mg/mL steamed berry extract (120 ¡C 2 hours), the anti-proliferation effects were 97.8% for HCT-116 and 99.6% for SW-480 cells.

After staining with Hoechst 33258, apoptotic cells increased significantly by treatment with steamed berry extract compared with unheated extracts. The steaming of American ginseng berries hence augments ginsenoside Rg3 content and increases the anti-proliferative effects on two human colorectal cancer cell lines (Wang et al., 2006).

Glioblastoma

The major active components in red ginseng consist of a variety of ginsenosides including Rg3, Rg5 and Rk1, each of which has different pharmacological activities. Among these, Rg3 has been reported to exert anti-cancer activities through inhibition of angiogenesis and cell proliferation.

It is essential to develop a greater understanding of this novel compound by investigating the effects of Rg3 on a human glioblastoma cell line and its molecular signaling mechanism. The mechanisms of apoptosis by ginsenoside Rg3 were related with the MEK signaling pathway and reactive oxygen species. These data suggest that ginsenoside Rg3 is a novel agent for the chemotherapy of GBM (Choi et al., 2013).

Colon Cancer; Chemotherapy

Rg3 can inhibit the activity of NF-kappaB, a key transcriptional factor constitutively activated in colon cancer that confers cancer cell resistance to chemotherapeutic agents. Compared to treatment with Rg3 or chemotherapy alone, combined treatment was more effective (i.e., there were synergistic effects) in the inhibition of cancer cell growth and induction of apoptosis and these effects were accompanied by significant inhibition of NF-kappaB activity.

NF-kappaB target gene expression of apoptotic cell death proteins (Bax, caspase-3, caspase-9) was significantly enhanced, but the expression of anti-apoptotic genes and cell proliferation marker genes (Bcl-2, inhibitor of apoptosis protein (IAP-1) and X chromosome IAP (XIAP), Cox-2, c-Fos, c-Jun and cyclin D1) was significantly inhibited by the combined treatment compared to Rg3 or docetaxel alone.

These results indicate that ginsenoside Rg3 inhibits NF-kappaB, and enhances the susceptibility of colon cancer cells to docetaxel and other chemotherapeutics. Thus, ginsenoside Rg3 could be useful as an anti-cancer or adjuvant anti-cancer agent (Kim et al., 2009).

Prostate Cancer; Chemo-sensitizer

Nuclear factor-kappa (NF-kappaB) is also constitutively activated in prostate cancer, and gives cancer cells resistance to chemotherapeutic agents. Rg3 has hence also been found to increase susceptibility of prostate (LNCaP and PC-3, DU145) cells against chemotherapeutics; prostate cancer cell growth as well as activation of NF-kappaB was examined. It has been found that a combination treatment of Rg3 (50 microM) with a conventional agent docetaxel (5 nM) was more effective in the inhibition of prostate cancer cell growth and induction of apoptosis as well as G(0)/G(1) arrest accompanied with the significant inhibition of NF-kappaB activity, than those by treatment of Rg3 or docetaxel alone.

The combination of Rg3 (50 microM) with cisplatin (10 microM) and doxorubicin (2 microM) was also more effective in the inhibition of prostate cancer cell growth and NF-kappaB activity than those by the treatment of Rg3 or chemotherapeutics alone. These results indicate that ginsenoside Rg3 inhibits NF-kappaB, and enhances the susceptibility of prostate cancer cells to docetaxel and other chemotherapeutics. Thus, ginsenoside Rg3 could be useful as an anti-cancer agent (Kim et al., 2010).

Colon Cancer

Ginsenosides may not only be useful in themselves, but also for their downstream metabolites. Compound K (20-O-( β -D-glucopyranosyl)-20(S)-protopanaxadiol) is an active metabolite of ginsenosides and induces apoptosis in various types of cancer cells. This study investigated the role of autophagy in compound K-induced cell death of human HCT-116 colon cancer cells. Compound K activated an autophagy pathway characterized by the accumulation of vesicles, the increased positive acridine orange-stained cells, the accumulation of LC3-II, and the elevation of autophagic flux.

Compound K-provoked autophagy was also linked to the generation of intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS); both of these processes were mitigated by the pre-treatment of cells with the anti-oxidant N-acetylcysteine. Moreover, compound K activated the c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase (JNK) signaling pathway, whereas down-regulation of JNK by its specific inhibitor SP600125 or by small interfering RNA against JNK attenuated autophagy-mediated cell death in response to compound K.

Notably, compound K-stimulated autophagy as well as apoptosis was induced by disrupting the interaction between Atg6 and Bcl-2. Taken together, these results indicate that the induction of autophagy and apoptosis by compound K is mediated through ROS generation and JNK activation in human colon cancer cells (Kim et al., 2013b).

Lung Cancer; SCC

Korea white ginseng (KWG) has been investigated for its chemo-preventive activity in a mouse lung SCC model. N-nitroso-trischloroethylurea (NTCU) was used to induce lung tumors in female Swiss mice, and KWG was given orally. KWG significantly reduced the percentage of lung SCCs from 26.5% in the control group to 9.1% in the KWG group and in the meantime, increased the percentage of normal bronchial and hyperplasia. KWG was also found to greatly reduce squamous cell lung tumor area from an average of 9.4% in control group to 1.5% in the KWG group.

High-performance liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry identified 10 ginsenosides from KWG extracts, Rb1 and Rd being the most abundant as detected in mouse blood and lung tissue. These results suggest that KWG could be a potential chemo-preventive agent for lung SCC (Pan et al., 2013).

Leukemia

Rg1 was found to significantly inhibit the proliferation of K562 cells in vitro and arrest the cells in G2/M phase. The percentage of positive cells stained by SA-beta-Gal was dramatically increased (P < 0.05) and the expression of cell senescence-related genes was up-regulated. The observation of ultrastructure showed cell volume increase, heterochromatin condensation and fragmentation, mitochondrial volume increase, and lysosomes increase in size and number. Rg1 can hence induce the senescence of leukemia cell line K562 and play an important role in regulating p53-p21-Rb, p16-Rb cell signaling pathway (Cai et al., 2012).

Leukemia, Lymphoma

It has been found that Rh2 inhibits the proliferation of human leukemia cells concentration- and time-dependently with an IC(50) of ~38 µM. Rh2 blocked cell-cycle progression at the G(1) phase in HL-60 leukemia and U937 lymphoma cells, and this was found to be accompanied by the down-regulations of cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) 4, CDK6, cyclin D1, cyclin D2, cyclin D3 and cyclin E at the protein level. Treatment of HL-60 cells with Rh2 significantly increased transforming growth factor- β (TGF- β ) production, and co-treatment with TGF- β neutralizing antibody prevented the Rh2-induced down-regulations of CDK4 and CDK6, up-regulations of p21(CIP1/WAF1) and p27(KIP1) levels and the induction of differentiation. These results demonstrate that the Rh2-mediated G(1) arrest and the differentiation are closely linked to the regulation of TGF- β production in human leukemia cells (Chung et al., 2012).

NSCLC

Ginsenoside Rh2, one of the components in ginseng saponin, has been shown to have anti-proliferative effect on human NSCLC cells and is being studied as a therapeutic drug for NSCLC. MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are small, non-coding RNA molecules that play a key role in cancer progression and prevention.

A unique set of changes in the miRNA expression profile in response to Rh2 treatment in the human NSCLC cell line A549 has been identified using miRNA microarray analysis. These miRNAs are predicted to have several target genes related to angiogenesis, apoptosis, chromatic modification, cell proliferation and differentiation. Thus, these results may assist in the better understanding of the anti-cancer mechanism of Rh2 in NSCLC (An et al., 2012).

Ginsenoside Concentrations

Ginsenosides, the major chemical composition of Chinese white ginseng (Panax ginseng C. A. Meyer), can inhibit tumor, enhance body immune function, prevent neurodegeneration. The amount of ginsenosides in the equivalent extraction of the nanoscale Chinese white ginseng particles (NWGP) was 2.5 times more than that of microscale Chinese white ginseng particles (WGP), and the extractions from NWGP (1000 microg/ml) reached a high tumor inhibition of 64% exposed to human lung carcinoma cells (A549) and 74% exposed to human cervical cancer cells (Hela) after 72 hours. Thia work shows that the nanoscale Chinese WGP greatly improves the bioavailability of ginsenosides (Ji et al., 2012).

Chemotherapy Side-effects

Pre-treatment with American ginseng berry extract (AGBE), a herb with potent anti-oxidant capacity, and one of its active anti-oxidant constituents, ginsenoside Re, was examined for its ability to counter cisplatin-induced emesis using a rat pica model. In rats, exposure to emetic stimuli such as cisplatin causes significant kaolin (clay) intake, a phenomenon called pica. We therefore measured cisplatin-induced kaolin intake as an indicator of the emetic response.

Rats were pre-treated with vehicle, AGBE (dose range 50–150 mg/kg, IP) or ginsenoside Re (2 and 5 mg/kg, IP). Rats were treated with cisplatin (3 mg/kg, IP) 30 min later. Kaolin intake, food intake, and body weight were measured every 24 hours, for 120 hours.

A significant dose-response relationship was observed between increasing doses of pre-treatment with AGBE and reduction in cisplatin-induced pica. Kaolin intake was maximally attenuated by AGBE at a dose of 100 mg/kg. Food intake also improved significantly at this dose (P<0.05). pre-treatment ginsenoside (5 mg/kg) also decreased kaolin intake >P<0.05). In vitro studies demonstrated a concentration-response relationship between AGBE and its ability to scavenge superoxide and hydroxyl.

Pre-treatment with AGBE and its major constituent, Re, hence attenuated cisplatin-induced pica, and demonstrated potential for the treatment of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. Significant recovery of food intake further strengthens the conclusion that AGBE may exert an anti-nausea/anti-emetic effect (Mehendale et al., 2005).

MDR

Because ginsenosides are structurally similar to cholesterol, the effect of Rp1, a novel ginsenoside derivative, on drug resistance using drug-sensitive OVCAR-8 and drug-resistant NCI/ADR-RES and DXR cells. Rp1 treatment resulted in an accumulation of doxorubicin or rhodamine 123 by decreasing MDR-1 activity in doxorubicin-resistant cells. Rp1 synergistically induced cell death with actinomycin D in DXR cells. Rp1 appeared to redistribute lipid rafts and MDR-1 protein.

Rp1 reversed resistance to actinomycin D by decreasing MDR-1 protein levels and Src phosphorylation with modulation of lipid rafts. Addition of cholesterol attenuated Rp1-induced raft aggregation and MDR-1 redistribution. Rp1 and actinomycin D reduced Src activity, and overexpression of active Src decreased the synergistic effect of Rp1 with actinomycin D. Rp1-induced drug sensitization was also observed with several anti-cancer drugs, including doxorubicin. These data suggest that lipid raft-modulating agents can be used to inhibit MDR-1 activity and thus overcome drug resistance (Yun et al., 2013).

Hypersensitized MDR Breast Cancer Cells to Paclitaxel

The effects of Rh2 on various tumor-cell lines for its effects on cell proliferation, induction of apoptosis, and potential interaction with conventional chemotherapy agents were investigated. Jia et al., (2004) showed that Rh2 inhibited cell growth by G1 arrest at low concentrations and induced apoptosis at high concentrations in a variety of tumor-cell lines, possibly through activation of caspases. The apoptosis induced by Rh2 was mediated through glucocorticoid receptors. Most interestingly, Rh2 can act either additively or synergistically with chemotherapy drugs on cancer cells. Particularly, it hypersensitized multi-drug-resistant breast cancer cells to paclitaxel.

These results suggest that Rh2 possesses strong tumor-inhibiting properties, and potentially can be used in treatments for multi-drug-resistant cancers, especially when it is used in combination with conventional chemotherapy agents.

MDR; Leukemia, Fibroblast Carcinoma

It was previously reported that a red ginseng saponin, 20(S)-ginsenoside Rg3 could modulate MDR in vitro and extend the survival of mice implanted with ADR-resistant murine leukemia P388 cells. A cytotoxicity study revealed that 120 microM of Rg3 was cytotoxic against a multi-drug-resistant human fibroblast carcinoma cell line, KB V20C, but not against normal WI 38 cells in vitro. 20 microM Rg3 induced a significant increase in fluorescence anisotropy in KB V20C cells but not in the parental KB cells. These results clearly show that Rg3 decreases the membrane fluidity thereby blocking drug efflux (Kwon et al., 2008).

MDR

Ginsenoside Rb1 is a representative component of panaxadiol saponins, which belongs to dammarane-type tritepenoid saponins and mainly exists in family araliaceae. It has been reported that ginsenoside Rb1 has diverse biological activities. The research development in recent decades on its pharmacological effects of cardiovascular system, anti-senility, reversing multi-drug resistance of tumor cells, adjuvant anti-cancer chemotherapy, and promoting peripheral nerve regeneration have been established (Jia et al., 2008).

Enhances Cyclophosphamide

Cyclophosphamide, an alkylating agent, has been shown to possess various genotoxic and carcinogenic effects, however, it is still used extensively as an anti-tumor agent and immunosuppressant in the clinic. Previous reports reveal that cyclophosphamide is involved in some secondary neoplasms.

C57BL/6 mice bearing B16 melanoma and Lewis lung carcinoma cells were respectively used to estimate the anti-tumor activity in vivo. The results indicated that oral administration of Rh(2) (5, 10 and 20 mg/kg body weight) alone has no obvious anti-tumor activity and genotoxic effect in mice, while Rh(2) synergistically enhanced the anti-tumor activity of cyclophosphamide (40 mg/kg body weight) in a dose-dependent manner.

Rh(2) decreased the micronucleus formation in polychromatic erythrocytes and DNA strand breaks in white blood cells in a dose-dependent way. These results suggest that ginsenoside Rh(2) is able to enhance the anti-tumor activity and decrease the genotoxic effect of cyclophosphamide (Wang, Zheng, Liu, Li, & Zheng, 2006).

Down-regulates MMP-9, Anti-metastatic

The effects of the purified ginseng components, panaxadiol (PD) and panaxatriol (PT), were examined on the expression of matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9) in highly metastatic HT1080 human fibrosarcoma cell line. A significant down-regulation of MMP-9 by PD and PT was detected by Northern blot analysis; however, the expression of MMP-2 was not changed by treatment with PD and PT. The results of the in vitro invasion assay revealed that PD and PT reduced tumor cell invasion through a reconstituted basement membrane in the transwell chamber. Because of the similarity of chemical structure between PD, PT and dexamethasone (Dexa), a synthetic glucocorticoid, we investigated whether the down-regulation of MMP-9 by PD and PT were mediated by the nuclear translocation of glucocorticoid receptor (GR). Increased GR in the nucleus of HT1080 human fibrosarcoma cells treated by PD and PT was detected by immunocytochemistry.

Western blot and gel retardation assays confirmed the increase of GR in the nucleus after treatment with PD and PT. These results suggest that GR-induced down-regulation of MMP-9 by PD and PT contributes to reduce the invasive capacity of HT1080 cells (Park et al., 1999).

Enhances 5-FU; Colorectal Cancer

Panaxadiol (PD) is the purified sapogenin of ginseng saponins, which exhibit anti-tumor activity. The possible synergistic anti-cancer effects of PD and 5-FU on a human colorectal cancer cell line, HCT-116, have been investigated.

The significant suppression on HCT-116 cell proliferation was observed after treatment with PD (25 microM) for 24 and 48 hours. Panaxadiol (25 microM) markedly (P < 0.05) enhanced the anti-proliferative effects of 5-FU (5, 10, 20 microM) on HCT-116 cells compared to single treatment of 5-FU for 24 and 48 hours.

Flow cytometric analysis on DNA indicated that PD and 5-FU selectively arrested cell-cycle progression in the G1 phase and S phase (P < 0.01), respectively, compared to the control condition. Combination use of 5-FU with PD significantly (P < 0.001) increased cell-cycle arrest in the S phase compared to that treated by 5-FU alone.

The combination of 5-FU and PD significantly enhanced the percentage of apoptotic cells when compared with the corresponding cell groups treated by 5-FU alone (P < 0.001). Panaxadiol hence enhanced the anti-cancer effects of 5-FU on human colorectal cancer cells through the regulation of cell-cycle transition and the induction of apoptotic cells (Li et al., 2009).

Colorectal Cancer

The possible synergistic anti-cancer effects of Panaxadiol (PD) and Epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG), on human colorectal cancer cells and the potential role of apoptosis in the synergistic activities, have been investigated.

Cell growth was suppressed after treatment with PD (10 and 20 µm) for 48 h. When PD (10 and 20 µm) was combined with EGCG (10, 20, and 30 µm), significantly enhanced anti-proliferative effects were observed in both cell lines. Combining 20 µm of PD with 20 and 30 µm of EGCG significantly decreased S-phase fractions of cells. In the apoptotic assay, the combination of PD and EGCG significantly increased the percentage of apoptotic cells compared with PD alone (p < 0.01).

Data from this study suggested that apoptosis might play an important role in the EGCG-enhanced anti-proliferative effects of PD on human colorectal cancer cells (Du et al., 2013).

Colorectal Cancer; Irinotecan

Cell cycle analysis demonstrated that combining irinotecan treatment with panaxadiol significantly increased the G1-phase fractions of cells, compared with irinotecan treatment alone. In apoptotic assays, the combination of panaxadiol and irinotecan significantly increased the percentage of apoptotic cells compared with irinotecan alone (P<0.01). Increased activity of caspase-3 and caspase-9 was observed after treating with panaxadiol and irinotecan.

Data from this study suggested that caspase-3- and caspase-9-mediated apoptosis may play an important role in the panaxadiol enhanced anti-proliferative effects of irinotecan on human colorectal cancer cells (Du et al., 2012).

Anti-inflammatory

Ginsenoside Re inhibited IKK- β phosphorylation and NF- κ B activation, as well as the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines, TNF- α and IL-1 β , in LPS-stimulated peritoneal macrophages, but it did not inhibit them in TNF- α – or PG-stimulated peritoneal macrophages. Ginsenoside Re also inhibited IRAK-1 phosphorylation induced by LPS, as well as IRAK-1 and IRAK-4 degradations in LPS-stimulated peritoneal macrophages.

Orally administered ginsenoside Re significantly inhibited the expression of IL-1 β and TNF- α on LPS-induced systemic inflammation and TNBS-induced colitis in mice. Ginsenoside Re inhibited colon shortening and myeloperoxidase activity in TNBS-treated mice. Ginsenoside Re reversed the reduced expression of tight-junction-associated proteins ZO-1, claudin-1, and occludin. Ginsenoside Re (20 mg/kg) inhibited the activation of NF- κ B in TNBS-treated mice. On the basis of these findings, ginsenoside Re may ameliorate inflammation by inhibiting the binding of LPS to TLR4 on macrophages (Lee et al., 2012).

Induces Apoptosis

Compound K activated an autophagy pathway characterized by the accumulation of vesicles, the increased positive acridine orange-stained cells, the accumulation of LC3-II, and the elevation of autophagic flux. Compound K activated the c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase (JNK) signaling pathway, whereas down-regulation of JNK by its specific inhibitor SP600125 or by small interfering RNA against JNK attenuated autophagy-mediated cell death in response to compound K. Compound K also provoked apoptosis, as evidenced by an increased number of apoptotic bodies and sub-G1 hypodiploid cells, enhanced activation of caspase-3 and caspase-9, and modulation of Bcl-2 and Bcl-2-associated X protein expression (Kim et al., 2013b).

Lung Cancer

AD-1, a ginsenoside derivative, concentration-dependently reduces lung cancer cell viability without affecting normal human lung epithelial cell viability. In A549 and H292 lung cancer cells, AD-1 induces G0/G1 cell-cycle arrest, apoptosis and ROS production. The apoptosis can be attenuated by a ROS scavenger – N-acetylcysteine (NAC). In addition, AD-1 up-regulates the expression of p38 and ERK phosphorylation. Addition of a p38 inhibitor, SB203580, suppresses the AD-1-induced decrease in cell viability. Furthermore, genetic silencing of p38 attenuates the expression of p38 and decreases the AD-1-induced apoptosis.

These data support development of AD-1 as a potential agent for lung cancer therapy (Zhang et al., 2013).

Pediatric AML

In this study, Chen et al. (2013) demonstrated that compound K, a major ginsenoside metabolite, inhibited the growth of the clinically relevant pediatric AML cell lines in a time- and dose-dependent manner. This growth-inhibitory effect was attributable to suppression of DNA synthesis during cell proliferation and the induction of apoptosis was accompanied by DNA double strand breaks. Findings suggest that as a low toxic natural reagent, compound K could be a potential drug for pediatric AML intervention and to improve the outcome of pediatric AML treatment.

Melanoma

Jeong et al. (2013) isolated 12 ginsenoside compounds from leaves of Panax ginseng and tested them in B16 melanoma cells. It significantly reduced melanin content and tyrosinase activity under alpha-melanocyte stimulating hormone- and forskolin-stimulated conditions. It significantly reduced the cyclic AMP (cAMP) level in B16 melanoma cells, and this might be responsible for the regulation down of MITF and tyrosinase. Phosphorylation of a downstream molecule, a cAMP response-element binding protein, was significantly decreased according to Western blotting and immunofluorescence assay. These data suggest that A-Rh4 has an anti-melanogenic effect via the protein kinase A pathway.

Leukemia

Rg1 can significantly inhibit the proliferation of leukemia cell line K562 in vitro and arrest the cells in G2/M phase. The percentage of positive cells stained by SA-beta-Gal was dramatically increased (P < 0.05) and the expression of cell senescence-related genes was up-regulated. The observation of ultrastructure showed cell volume increase, heterochromatin condensation and fragmentation, mitochondrial volume increase, and lysosomes increase in size and number (Cai et al., 2012).

Ginsenosides and CYP 450 Enzymes

In vitro experiments have shown that both crude ginseng extract and total saponins at high concentrations (.2000 mg/ml) inhibited CYP2E1 activity in mouse and human microsomes (Nguyen et al., 2000). Henderson et al. (1999) reported the effects of seven ginsenosides and two eleutherosides (active components of the ginseng root) on the catalytic activity of a panel of cDNA-expressed CYP isoforms (CYP1A2, CYP2C9, CYP2C19, CYP2D6, and CYP3A4) using 96-well plate fluorometrical assay.

Of the constituents tested, Ginsenoside Rd caused weak inhibitory activity against CYP3A4, CYP2D6, CYP2C19,and CYP2C9, but ginsenoside Re and ginsenoside Rf (200 mM) produced a 70% and 54%increase in the activity of CYP2C9 and CYP3A4, respectively. The authors suggested that the activating effects of ginsenosides on CYP2C9 and CYP3A4 might be due to a matrix effect caused by the test compound fluorescing at the same wavelength as the metabolite of the marker substrates. Chang et al. (2002) reported the effects of two types of ginseng extract and ginsenosides (Rb1, Rb2, Rc, Rd, Re, Rf, and Rg1) on CYP1 catalytic activities.

The ginseng extracts inhibited human recombinant CYP1A1, CYP1A2, and CYP1B1 activities in a concentration-dependent manner. Rb1, Rb2, Rc, Rd, Re, Rf, and Rg1 at low concentrations had no effect on CYP1 activities, but Rb1, Rb2, Rc, Rd, and Rf at a higher ginsenoside concentration (50 mg/ml) inhibited these activities. These results indicated that various ginseng extracts and ginsenosides inhibited CYP1 activity in an enzyme-selective and extract-specific manner (Zhou et al., 2003).

References

An IS, An S, Kwon KJ, Kim YJ, Bae S. (2012). Ginsenoside Rh2 mediates changes in the microRNA expression profile of human non-small-cell lung cancer A549 cells. Oncol Rep, 29(2):523-8. doi: 10.3892/or.2012.2136.

Bae EA, Han MJ, Choo MK et al. (2002). Metabolism of 20(S)- and 20(R)-ginsenoside R-g3 by human intestinal bacteria and its relation to in vitro biological activities. Biol. Pharm. Bull, 25:58–63.

Cai S, Zhou Y, Liu J, et al. (2012). Experimental study on human leukemia cell line K562 senescence induced by ginsenoside Rg1. Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi, 37(16):2424-8.

Cao M, Yu HS, Song XB, Ma BP. (2012) Advances in the study of derivatization of ginsenosides and their anti-tumor structure-activity relationship. Yao Xue Xue Bao, 47(7):836-43.

Chang TKH, Chen J, Benetton SA et al. (2002). In vitro effect of standardized ginseng extracts and individual ginsenosides on the catalytic activity of human CYP1A1, CYP1A2, and CYP1B1. Drug Metab. Dispos, 30:378–384.

Chen Y, Xu Y, Zhu Y, Li X. (2013). Anti-cancer effects of ginsenoside compound k on pediatric acute myeloid leukemia cells. Cancer Cell Int, 13(1):24. doi: 10.1186/1475-2867-13-24.

Choi YJ, Lee HJ, Kang DW, et al. (2013). Ginsenoside Rg3 induces apoptosis in the U87MG human glioblastoma cell line through the MEK signaling pathway and reactive oxygen species. Oncol Rep, 30(3): 1362-1370. doi: 10.3892/or.2013.2555.

Christensen LP. (2009). Ginsenosides chemistry, biosynthesis, analysis, and potential health effects. Adv Food Nutr Res., 55:1-99. doi: 10.1016/S1043-4526(08)00401-4.

Chung KS, Cho SH, Shin JS, et al. (2013). Ginsenoside Rh2 induces Cell-cycle arrest and differentiation in human leukemia cells by upregulating TGF- β expression. Carcinogenesis, 34(2):331-40. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgs341.

Du GJ, Wang CZ, Zhang ZY, et al. (2012) Caspase-mediated pro-apoptotic interaction of panaxadiol and irinotecan in human colorectal cancer cells. J Pharm Pharmacol, 64(5):727-34. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.2012.01463.x.

Du GJ, Wang CZ, Qi LW, et al. (2013). The synergistic apoptotic interaction of panaxadiol and epigallocatechin gallate in human colorectal cancer cells. Phytother Res, 27(2):272-7. doi: 10.1002/ptr.4707.

Henderson GL, Harkey MR, Gershwin, ME, et al. (1999). Effects of ginseng components on c-DNA-expressed cytochrome P450 enzyme catalytic activity. Life Sci, PL209–PL214.

Jeong YM, Oh WK, Tran TL, et al. (2013). Aglycone of Rh4 inhibits melanin synthesis in B16 melanoma cells: possible involvement of the protein kinase A pathway. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem, 77(1):119-25.

Ji Y, Rao Z, Cui J, et al. (2012). Ginsenosides extracted from nanoscale Chinese white ginseng enhances anti-cancer effect. J Nanosci Nanotechnol, 12(8):6163-7.

Jia WW, Bu X, Philips D, et al. (2004). Rh2, a compound extracted from ginseng, hypersensitizes Multi-drug-resistant tumor cells to chemotherapy. Can J Physiol Pharmacol, 82(7):431-7.

Jia JM, Wang ZQ, Wu LJ, Wu YL. (2008). Advance of pharmacological study on ginsenoside Rb1. Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi, 33(12):1371-7.

Kim YJ, Yamabe N, Choi P, et al. (2013a) Efficient Thermal Deglycosylation of Ginsenoside Rd and Its Contribution to the Improved Anti-cancer Activity of Ginseng. J Agric Food Chem.

Kim AD, Kang KA, Kim HS, et al. (2013b). A ginseng metabolite, compound K, induces autophagy and apoptosis via generation of reactive oxygen species and activation of JNK in human colon cancer cells. Cell Death Dis, 4:e750. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2013.273.

Kim SM, Lee SY, Cho JS, et al. (2010). Combination of ginsenoside Rg3 with docetaxel enhances the susceptibility of prostate cancer cells via inhibition of NF-kappaB. Eur J Pharmacol, 631(1-3):1-9. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2009.12.018.

Kim SM, Lee SY, Yuk DY, et al. (2009). Inhibition of NF-kappaB by ginsenoside Rg3 enhances the susceptibility of colon cancer cells to docetaxel. Arch Pharm Res, 32:755–765. doi: 10.1007/s12272-009-1515-4.

King ML, Adler SR, Murphy LL. (2006). Extraction-dependent effects of American ginseng (Panax quinquefolium) on human breast cancer cell proliferation and estrogen receptor activation. Integr Cancer Ther, 5(3):236-43.

Kwon HY, Kim EH, Kim SW, et al. (2008). Selective toxicity of ginsenoside Rg3 on Multi-drug-resistant cells by membrane fluidity modulation. Arch Pharm Res, 31(2):171-7.

Lee IA, Hyam SR, Jang SE, Han MJ, Kim DH. (2012). Ginsenoside Re ameliorates inflammation by inhibiting the binding of lipopolysaccharide to TLR4 on macrophages. J Agric Food Chem, 60(38):9595-602.

Li XL, Wang CZ, Mehendale SR, et al. (2009). Panaxadiol, a purified ginseng component, enhances the anti-cancer effects of 5-fluorouracil in human colorectal cancer cells. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol, 64(6):1097-104. doi: 10.1007/s00280-009-0966-0.

Mehendale S, Aung H, Wang A, et al. (2005). American ginseng berry extract and ginsenoside Re attenuate cisplatin-induced kaolin intake in rats. Cancer Chemotherapy and Pharmacology, 56(1):63-9. doi: 10.1007/s00280-004-0956-1.

Nguyen TD, Villard PH, Barlatier A et al. (2000). Panax vietnamensis protects mice against carbon tetrachloride-induced hepatotoxicity without any modification of CYP2E1 gene expression. Planta Med, 66:714–719.

Pan J, Zhang Q, Li K, et al. (2013). Chemoprevention of lung squamous cell carcinoma by ginseng. Cancer Prev Res (Phila), 6(6):530-9. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-12-0366.

Park MT, Cha HJ, Jeong JW, et al. (1999). Glucocorticoid receptor-induced down-regulation of MMP-9 by ginseng components, PD and PT contributes to inhibition of the invasive capacity of HT1080 human fibrosarcoma cells. Mol Cells, 9(5):476-83.

Wang CZ and Yuan CS. (2008). Potential Role of Ginseng in the Treatment of Colorectal Cancer. Am. J. Chin. Med, 36:1019. doi: 10.1142/S0192415X08006545

Wang Z, Zheng Q, Liu K, Li G, Zheng R. (2006). Ginsenoside Rh(2) enhances anti-tumor activity and decreases genotoxic effect of cyclophosphamide. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol, 98(4):411-5.

Wang CZ, Zhang B, Song WX, et al. (2006). Steamed American ginseng berry: ginsenoside analyzes and anti-cancer activities. Journal of agricultural and food chemistry, 54(26):9936-42.

Yun UJ, Lee JH, Koo KH, et al. (2013). Lipid raft modulation by Rp1 reverses Multi-drug resistance via inactivating MDR-1 and Src inhibition. Biochem Pharmacol, 85(10):1441-53. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2013.02.025.

Zhang LH, Jia YL, Lin XX, et al. (2013). AD-1, a novel ginsenoside derivative, shows anti-lung cancer activity via activation of p38 MAPK pathway and generation of reactive oxygen species. Biochim Biophys Acta, 1830(8):4148-59. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2013.04.008.

Zhou Sf, Gao Yh, Jiang Wq et al. (2003) Interactions of Herbs with Cytochrome P450. DRUG METABOLISM REVIEWS, 35(1):35–98.